Crop adapted to dry, nutrient-poor soils matures faster

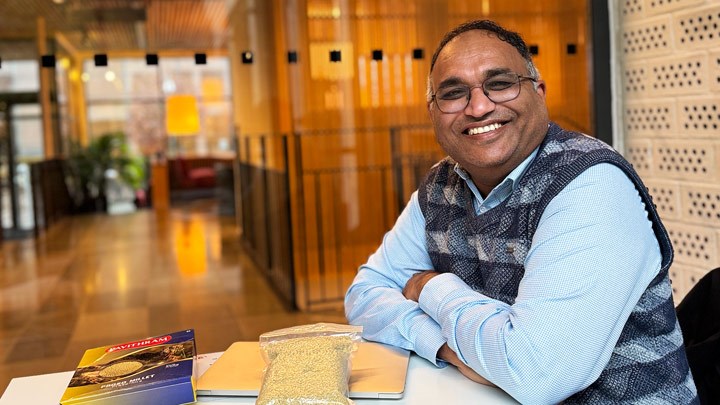

“Proso millet grows in dry soils and requires no pesticides or fertilisers,” says Selvaraju Kanagarajan. In Sweden, millet is available in airtight packaging as it otherwise has a short shelf life.

Sowing to harvest can be shortened from 90 to 60 days “We saw that photosynthesis was much more efficient in a certain variety of the crop,” says Selvaraju Kanagarajan, a researcher in biology at Örebro University.

The study, now published in the highly ranked journal BMC Plant Biology, focuses on proso millet (Panicum miliaceum), a crop that is the staple food for 90 million people in Africa and Asia, according to UN estimates. Climate change has made millet more interesting for several reasons.

“Proso millet is a traditional crop that grows on dry and nutrient-poor soils. It does not require pesticides or fertilisers,” says Selvaraju Kanagarajan.

In the project, the researchers used a wild variety of millet and a mutant variety to compare how photosynthesis works – the process that enables plants to produce their own nutrients and oxygen.

The results showed that the mutant variety matured faster and produced higher yields due to more efficient photosynthesis. The researchers identified 42 genetic markers based on DNA sequences, 11 of which were unique to the mutant proso millet.

“We can use our knowledge of these markers in further studies to identify the genetic variants of proso millet that produce the best yield,” says Selvaraju Kanagarajan.

A future crop in the wake of climate change

The study focuses on how the entire DNA structure, or genome, affects photosynthesis in proso millet. But photosynthesis is not the only determining factor.

“To get the full picture, we also need to include nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA to see if the markers we’ve identified are linked to higher yields. We’ve found some genes that appear to be important, and the plan is to investigate whether these genes affect yields.”

This is the next step in the work to see if proso millet can become a more important crop in the wake of climate change. In addition to growing on dry, nutrient-poor soils without pesticides or fertilisers, the study shows that the time between sowing and harvest can be reduced from 3 months to 2.

Selvaraju Kanagarajan sees millet as an alternative to rice, a staple of Indian cuisine. Rice is one of the most water-intensive crops, even with modern technology. According to Kanagarajan, increasing millet intake would benefit public health in India.

“Rice and wheat consumption is also one of the reasons for the rise in diabetes in India. Proso millet could be an alternative that many people could grow, even in their own backyards,” concludes Selvaraju Kanagarajan.

The United Nations has designated 2023 as the “International Year of Millets”.

Proso millet (Panicum miliaceum) grows on dry and nutrient-poor soils – a key characteristic in parts of India and several African countries, for example.

Millet is a collective name for several species in the grass family that produce small, edible seeds. Proso millet is also known as common millet, broomcorn millet, hog millet, Kashfi millet, red millet, and white millet.

It is nutritionally similar to wheat and other grains but does not contain gluten. One disadvantage is that its shelf life is shorter than that of wheat and rice.

According to the UN, some 90 million people in Africa and Asia depend on these seeds for their daily nutrition. Millet is also an important crop in China’s dry regions.

Text: Maria Elisson

Photo: Maria Elisson

Translation: Jerry Gray